Great is the might of the Meaningless! Especially in a rattling refrain or a rousing chorus. Big drum effects are always popular. What wonder clever Miss LOTTIE COLLINS'S "Ta-ra-ra-boom-de-ay!" is all the rage? "Her greatest creation" (vide advertisements), "sung and danced with the utmost verve," has taken the town. Will it "mar its use" to attach a meaning to it? Let us try:—

No. VI.—THAT'S HOW WE BOOM TO-DAY!

I.

A SMART "mug-lumberer" one must be

To-day, to "fetch" Sassiety;

Not too strict, of swagger free,

And as "fly" as "fly" can be.

Ever pushing, ever bold,

(Else one's left "out in the cold")

Thus Success you grasp, and hold.

And may sing, though Pecksniffs scold,—

Chorus.

Tra-la! We "boom" to-day!

That's how we "boom" to-day!

Bra-va! We "boom" to-day!

Hoo-rah! We "boom" to-day!

[And so on, six times or more.

II.

All want to "Boom." But don't be shy,

For modesty is all my eye.

Shun all reserve, if you would try

For "paying" notoriety.

If you would "make your pile" in haste,

You must not bother about "taste."

Every chance must be embraced,

If you would sing when fairly "placed,"

Chorus—Tra-la! We "boom" to-day!

[Over and over again.

III.

Art's a good game. 'Tis easier far

Than 'twas of old to be a Star.

Hit on some trick crepuscular,

Like smudge or smoke, and there you are!

They'll mouth, and call you "Master." So

You're sure—in time—to be a go.

You will catch on, and sell, although

Your meaning not a soul may know,—

Chorus—Tra-la-la! "Boom" to-day!

[Ad libitum.

IV.

If Humour is your little line,

Coherent sense you must resign,

Cry, "Paradox alone's divine!

LAMB had his manner, this is Mine!"

Try strain and twist; gnaw the dry bone

Of mirth till all the marrow's gone;

And crowds, who first stared like a stone,

Your "subtle genius" soon will own.

Chorus—Tra-la! We "boom" to-day!

[Ad nauseam.

V.

Is the Dramatic "biz" preferred?

There you may "boom" it like a bird.

Turn on the Absolute-Absurd;

By that strange tap the mob is stirred.

Be dismal, deathly, dirty, dim;

Grovelling, ghastly, gruesome, grim,

Anything meaning morbid whim;

Quidnuncs will cry, "What treuth! what vim!"

Chorus—Tra-la-la! "Boom" to-day!

[As long as you like!

VI.

Or would you even higher fly,

And found a "Cult"? You've but to try.

That blend fools follow in full cry,

Meaninglessness plus Mystery!

A witch astride upon a broom,

A bogie in a darkened room,

Nonsense and nubibustic gloom,—

Mix them like witch-broth; they will "boom"!

Chorus—Tra-la! We "boom" to-day!

[Till you are tired of it.

VII.

Boom! Boom! 'Twill bring in cent. per cent.,

With that Big Drum, Advertisement.

Nonsense, with nous discreetly blent,

Finds the world cheated—and content.

But "make your game" while yet there's room,

For novel shapes of quackery. Doom

Awaits us in the outer gloom:

A day may come when Bosh won't "Boom"!

Chorus.

That's how we "boom" to-day!

Tra-la! We "boom" to-day!

Ha-ha! We "boom" to-day!

Tra-la! We "boom" to-day!

[And so on till further orders.

OUR BOOKING-OFFICE.—Quoth one of the Baron's Assistants to his Chief, "Sir, those who love the personality, and venerate the memory of CHARLES DICKENS, will thank Miss HOGARTH who has selected, Mr. LAWRENCE HUTTON who has edited, and OSGOOD, MCILVAINE & CO. who publish, a series of letters addressed by BOZ to WILKIE COLLINS. They bear date between the years 1851 and 1870, were found among COLLINS'S papers after his death, and prove not the least precious of his possessions. Foster's Life of Dickens will undoubtedly remain the medium through which the outer world shall know the great novelist." "True," interposes the Baron, "that certainly is one way in which admiration for the works of the great novelist will be foster'd among us. You agree? Of course you do. Proceed, sweet warbler, your observations interest me much." Whereupon the warbler thus addressed continued. "But, Sir, we are all conscious of a certain unpleasant taste those volumes leave in the mouth. Some of the incidents recorded, and many of the letters, present DICKENS with undue prominence in a possible phase of his character, as a ruthless tradesman in literature and lecturing, with some tendency to be overbearing in his social relations. In this little volume of letters to his old familiar friend we find him at his best, whether as a worker in literature or as a critic of other people's work."

BARON DE BOOKWORMS & CO.

"WITH RAVISHED EARS,

THE MONARCH HEARS,

ASSUMES THE GOD,

AFFECTS TO NOD,

AND SEEMS TO SHAKE THE SPHERES!"

OR, THE POWER OF SOUND.

(An Ode for the Brandenburg Diet Day; a long way after Dryden.)

["At the banquet of the Diet of Brandenburg, the GERMAN EMPEROR said:—'The assured knowledge that your sympathy loyally attends me in my work, inspires me with fresh strength to persevere in my task, and to advance along the path marked out for me by Heaven. To this are added the sense of responsibility to our Supreme Lord above, and my unshakable conviction that He, our former ally at Rossbach and Dennewitz, will not leave me in the lurch. He has taken such infinite pains with our ancient Brandenburg and our House, that we cannot suppose he has done this for no purpose.... My course is the right one, and it will be persevered in."—Daily Paper.]

'Twas in the royal feast Brandenburg set

For Providence's pet:

Aloft in Teuton state

The god-like hero sate

On his Imperial throne:

His Brandenburgers listened round,

Appreciative of the Power of Sound;

All admire shouting—when the Shouter's crowned!

The Jovian Eagle at his side

Perched, and like Rheims's Jackdaw, eyed

The Olympian hero in his pride.

Happy, happy, happy Chief!

None but the loud,

None but the loud,

From the crass crowd may win belief!

His looks he shook, his long moustache he twirled,

And saw a vision of himself as Sovereign of the World!

The listening crowd admire the lofty sound.

"A present deity!" they shout around.

"A present deity!" the vaulted roofs rebound.

With ravished ears,

The monarch hears,

Assumes the god,

Affects to nod,

And seems to shake the spheres!

In praise of Brandenburg the Shouting Emperor spoke,

In language like a huge thrasonic joke.

The newest god in triumph comes;

Blare the trumpets, thump the drums:

Flushed with a purple grace,

He lifts his Jovian face!

Now give the blowers breath. He comes, he comes!

New ALEXANDER fair and young,

Drinking, in Teuton nectar, once again

To Brandenburg, that treasure

Of earth, and heaven's chief pleasure,

Rich the treasure,

Sweet the pleasure,

Which to the gods has given such pain!

Soothed with the sound, the Emperor grows vain,

Fights all his battles o'er again;

'Twas Heaven that routed all his foes, Olympus slew his slain.

He has the greatest of allies!

Doubters are dastards in his eyes,

And grumblers at their deified

Young Emperor in his proper pride.

Should shake from their false shoes

Germania's dust. The Muse

Must sing Jove-WILHELM great and good,

By a benignant fate

Lifted, gifted, gifted, lifted,

Lifted to a god's estate,

Olympian in his mood:

* * * * *

The mighty Master smiled to see,

Infant-in-Arms, young Germany,

Jove's nursling, quit his cot and pap,

And, quite a promising young chap,

Grown out of baby-shoes and bottle,

And "draughts" which teased his infant throttle,

Get rid of ailments, tum-tum troubles,

Tooth-cutting pangs, and "windy" bubbles,

A tremendous time beginning;

Fighting still, all foes destroying:—

"A world-empire's worth the winning!

Its fair foretaste I'm enjoying.

The new god now sits beside ye,

Take the gifts he will provide ye!

He's your young Orbilian schooler,

Your Hereditary Ruler!"

(The Brandenburgers bellow loud applause.)

"My course is right, and glorious is my Cause!!!"

The Prince, the god unable to restrain,

Rose from his chair,

With Jovian air,

And, hanging up his thunderbolts with care,

What time his eagle gave a gruesome glare,

The nectar gulped again and yet again:

Then stooping his horned helmet firm to jam on,

Voted himself the New God—Jupiter-(G)Ammon!

* * * * *

"Let ALEXANDER yield the prize

To WILHELM of the Iron Crown;

He raised himself unto the skies,

I bring Olympus down!!!"

No. XI.—TO PLAUSIBILITY.

MY DEAR PLAU,

I SHOULD be the most ungrateful dog if I failed to acknowledge the pleasure I have received during my life from the society of your friends and protégés. I don't speak of mere material, meat-and-money advantages. Probably, if a strict account could be stated, it might be found that in these paltry matters a balance, large or small, was still due to me. Who knows? Strict accounts are hateful; and even if I did lose here and there I did it, I fancy, with my eyes open, and was not sorry to indulge these gentlemen with the idea that their fascinations had conquered me. No. What I speak of is rather the genuine pleasure I have derived from some of the finest acting (in ordinary life, not on the boards) that the world ever saw, acting in which I protest that the tears, the sighs, the misery, the gallantry, the courage, the loyal sentiments and the honourable promises all rang with so sincere a sound that the very actor himself was subdued like the dyer's hand to the colours he worked in, until he believed himself to be the most unjustly persecuted of mankind, the most upright of gentlemen, or whatever the special emotion he simulated required that he should seem to be for the moment. That he might possibly be what, as a matter of fact, he often was, a rogue and a knave, mattered little to me at the time. He was evidently himself ignorant of his potentialities, and in any case they could not spoil my æsthetic enjoyment of a notable performance. And after all who is to undertake to draw the line between the good man and the bad? I have known men with regard to whom I was convinced that they were admirably equipped by nature for a career of roguery; somewhere in the backs of their heads I know they carried a complete set of intellectual implements for the task, but no temptation, as it happened, ever came to open the door of that secret chamber, and the unconscious owners of it passed through life honoured by their fellow-citizens, and their actions still smell sweet and blossom in their dust. Others, of course, were not so fortunate. Their crisis pursued and captured them, revealed them to themselves and others, and in many cases only left them, alas, after cropping both their hair and their reputations. But I leave these divagations, which can have but little interest for you. What I rather wish to do is to recall to your memory the curious personality and the chequered adventures of our common friend, WILFRID COBBYN.

I met him some six years ago when I was on a visit to my father's old friend, General TEMPEST, at Dansington. Most people, I take it, have heard of Dansington, that home of educational establishments, amusement, and retired Indian Generals. Old General TEMPEST—LEONIDAS MARLBOROUGH TEMPEST he had been christened by a warlike father, whose military aspirations had been crushed by the necessity for a commercial career, and who had taken it out of fate by devoting his son to heroism at the baptismal font, and by subsequently buying him a commission in a crack regiment—General TEMPEST was, in the days of which I speak, a hospitable veteran whose amiability and good-nature had survived many severe campaigns in which he had taken and given hard knocks wherever hard knocks were to be found. His benevolence and hospitality were proverbial far beyond the limits of Dansington, and his daughter CLARA was one of the prettiest girls in the United Kingdom.

On the occasion of this visit I found a fellow guest, the identical WILFRID COBBYN whom I have already mentioned. He had been there for a fortnight, I learnt from ALEXANDER, the eldest hope of the TEMPESTS, and had made himself a favourite with every member of the family. How they got to know him I never quite discovered—indeed, I doubt if any of them could have told me—and as to his previous history all they seemed to know was that his father had property "somewhere in the West of England," that he himself had travelled a great deal, and was now close upon thirty years old. I am free to admit that after my first dinner in his company I had very little inclination to worry myself about the details of his past, so cheerful and fascinating did I find his gay companionship. I cannot quite explain the charm of the man. He had a roving blue eye, a ruddy and glowing complexion, and a laugh that seemed to kick all gloomy fancies into flinders, and to carry those who heard it in a helter-skelter gallop of mirth. And then what stories the fellow could tell! He had the General and me in perpetual convulsions, and even ALEXANDER, a somewhat awkward and taciturn youth, much weighed down by the responsibilities of his freshmanhood at Oxford, was pleased to unbend and smile approvingly at the amazing sallies of the wizard COBBYN.

One story I remember in particular, though I dare not attempt to repeat it as COBBYN told it. It was about the wretched adventures of a certain travelling companion of his on a shooting expedition in Albania. It was a story that never seemed to cease,—a bad recommendation for most stories, I admit; but in this case so artfully and with such surprising humour and force was it told, so vividly did it depict a long series of ludicrous sufferings culminating in the total loss of the sufferer's clothes and his involuntary appearance in the full uniform of a Turkish Zaptieh, with other surprising and endless episodes, that at the last we had in the midst of our gasps of helpless laughter to implore the narrator to stop for the sake of our sides and the resounding rafters of the General's house.

At other times the irresistible WILFRID would pose reminiscently as the gallant protector of outraged virtue, or as the hero of some deathless story of courage and coolness by which empires had been saved from disaster. And he was so persuasive, so convincing, that our imaginations, which would have refused to follow a smaller man on lower flights, soared obediently after him through an empyrean of impossible romance. Nor did he stop at this. General TEMPEST was the pattern of old-world punctilio, but before a week was out he had introduced COBBYN, of whom he knew nothing except what COBBYN told him, to all the best people in Dansington; nor shall I ever forget the air with which this glorious rascal took the portly old Countess of CARDAMUMS down to her second supper at the County Ball. He rode ALEXANDER'S chestnut, and ALEXANDER never murmured. The General's ancient retainer went on his many errands, and neither the General nor his man saw anything out of the way in the proceeding. Even CLARA looked, I thought, with some favour—but as CLARA always breaks into indignant denials whenever this is hinted, I will proceed no further. As for the members of the Dansington Club they were enthusiastic in COBBYN'S praises. The young sparks imitated his fashions in ties and collars, the old bucks repeated to one another his stories, and one and all vowed he was "an uncommon good fellow, by Gad."

To me COBBYN was always profusely polite, with that flattering politeness which induces the flattered to think himself just a shade cleverer and sharper and better than his fellow-creatures, and on the day before my departure he honoured me by borrowing a ten-pound note of me and writing my London address with much ceremony on the back of an envelope, which I afterwards found lying about in a passage of the General's house.

Three months afterwards there was a tempest in Dansington. COBBYN had gone away for two days and had stayed away for good. His intimates and the Dansington tradesmen became uneasy, rumours began to spread, and the result was a crash which made some very knowing fellows look extremely foolish, and filled the Club with honest British imprecations. Little TOM SPINDLE, who commanded a troop of the Fallowshire Yeomanry (the Duke of DASHBOROUGH'S Hussars) and had the reputation of spending a royal income with beggarly meanness, had backed one of COBBYN'S bills for £1,000. Sir PAUL PACKTHREAD, one of the greatest of the local magnates, had lent him £500 without a scrap of security, and Colonel CHUTNEY had put £300 into the Ephemeral Soapsuds Company, Limited, of which COBBYN was to have been the managing director. I cannot go through the whole long list. He had fleeced all that was fleeceable in Dansington, and had vanished into the clouds. How he managed to do it, by what artful proposals he conquered the avarice of SPINDLE, prevailed over the mercantile sagacity of PACKTHREAD, and subdued the fiery temper of CHUTNEY, will never be known. Partly, no doubt, he succeeded by being here and there perfectly truthful and candid. He was the son of a well-to-do country Squire, but the father had long since ejected his offspring from the paternal mansion; he had really travelled and had often displayed pluck. But his chief gifts were his good-humour, his ardent imagination, and a persuasive tongue that gained for him the trusting confidence of his victims almost before he himself knew that he meant to victimise them.

They tell me he is now established somewhere in the West of America. Wherever he goes he is sure to be popular—for a time.

Goodbye, dear old PLAU!

I hope I haven't bored you.

Yours trustfully,

SCENE—A Theatre with Audience and Company complete. The former "smart" and languidly enthusiastic, the last wearily looking forward to the final "Curtain." The last Act is all but over.

Servant (to Countess). The Duchess of BATTERSEA is in the Hall. May she come up?

Countess. Certainly. Why did you not show her up at once?

Servant (arranging his powdered hair in a glass). Because in cases of exposure her Grace is quite equal to showing up herself!

Countess (smiling). You are cynical, JOHN. Do you not know that cynicism is the birthright of fools, and, when discovered, is more than half found out?

Servant (taking up coal scuttle). Like the hair of your Lady-ship—out of curl! [Exit.

Countess. A quaint conceit; but here is my husband. Let me avoid him. A married man is quite out of date—save when he forms the subject of his own obituary. [Exit.

A pause. Enter the Duchess of BATTERSEA.

Duchess. Dear me! No one here! So I might have brought the Duke with me, after all! And yet he is so fond of the petticoats. He loses his head when he begins kissing his hand. And I lose my head when I fail to catch a 'buss. A kiss with him and a 'buss with me—where's the difference?

Enter Earl PENNYPLAINE.

Earl (angrily). You here!

Duchess (with an appealing gesture). You are not pleased to see me! You regard me as an adventuress! You are ashamed of my past! A past unblessed by a clergyman—in fact, a past without a pastor!

Earl. Begone! Do not dare to darken my doors again. This is no home for old jokes!

Duchess. You must hear me. Do you know why I have treated you so badly? Do you know why I have taught your wife to regard me as a rival? Why I have blackmailed you to the tune of hundreds of thousands of pounds? Do you know why I have done all this and more? I will tell you. Because I am your Mother-in-law!

QUITE TOO-TOO PUFFICKLY PRECIOUS!!

Being Lady Windy-mère's Fan-cy Portrait of the new dramatic author, Shakspeare Sheridan Oscar Puff, Esq.

["He addressed from the stage a public audience, mostly composed of ladies, pressing between his daintily-gloved fingers a still burning and half-smoked cigarette."—Daily Telegraph.]

Earl (in a choking voice). I suspected as much from the very first!

Re-enter the Countess, carrying a heap of family portraits.

Countess. Here, Duchess, although you are not to my liking, I have brought you a few pictures of my husband and some of his predecessors. Take 'em, and bless you!

Duchess (overflowing with emotion). My dear, this is too much. (Weeps.) You unwoman—I should say unlady—me!

Enter Lord TUPPENCE CULLARD.

Lord T.C. Come and marry me.

Duchess. With pleasure! Lawks-a-mussy! [Exeunt.

Earl. And now, let us remember that while the sun shines, the moon clings like a frightened thing to the face of CLEOPATRA.

Quick Curtain.

Applause follows, when enter the Author. He holds between his thumb and forefinger a lighted cigarette.

Author. Ladies and Gentlemen, it is so much the fashion nowadays to do what one pleases, that I venture to offer you some tobacco while I enjoy a smoke myself. (Throws cigars and cigarettes amongst the audience à la HARRY PAYNE.) Will you forgive me if I change my tail-coat for a smoking jacket? Thank you! (Makes the necessary alteration of costume in the presence of the audience.) And now I will have a chair. (Stamps, when up comes through a trap a table supporting a lounge), and a cup of tea. (Another table appears through another trap, bringing up with it a tray and a five o'clock set.) And now I think we are comfortable. (Helps himself to tea, smokes, &c.) I must tell you I think my piece excellent. And all the puppets that have performed in it have played extremely well. I hope you like my piece as well as I do myself. I trust you are not bored with this chatter, but I am not good at a speech. However, as I have to catch a train in twenty minutes, I will tell you a story occupying a quarter of an hour. I repeat, as I have to catch a train—I repeat, as I have to catch a train—

Entire Audience. And so have we! [Exeunt. (Thus the Play ends in smoke.)

(Rather more than a Fairy Story.)

JOHN SMITH, of London, sat in front of his fire pondering over the fact that, at a great sacrifice to the interests of his native city, the coal dues had been abolished, and yet his bill for fuel was no lighter. He watched the embers as they died away, when all of a sudden a small creature appeared before him. He could not account for her presence, and did not notice from whence she came. But she was there, sure enough, and began to address him.

"JOHN SMITH, of London," she began, in a small but admirably distinct voice, "I am the Fairy Domestic Economy, and I have come to warn you that, unless you wake up, you will come to grief."

"Wake up?" queried J.S. "Wake up about what?"

"Why, the election of the London County Council, to be sure!" returned the Fairy, impatiently. "Here, the election is close upon you, and the chances are twenty to one that you will let it pass without recording your vote." "What election?"

"Bless the man!" exclaimed the Fairy. "He does not know that the Members of the L.C.C., the Masters of London, are to be chosen on Saturday, the 5th of March, and will from that date remain in power for four years!"

And then the Fairy showed him the possible future, explaining that it was in his hands to alter it. The vision she conjured up before him seemed intensely idiotic. Everything was to be done for nothing. There were to be free railways, free tramways, free bakeries, free butchers' shops, free ginger-beer manufactories, free clothiers, free hosiers, free boot-makers, free gas companies, free waterworks—in fact, everything was to be gratis.

"But somebody must pay for it!" said JOHN SMITH, of London.

"Why, of course," returned the Fairy, "and you are to be the paymaster. You will have to pay about five shillings in the pound as a commencement, with additional crowns to follow!"

"But how am I to avoid this fate?" cried JOHN SMITH, in a tone of genuine alarm.

"By voting for the Moderates, and doing your best to keep out the Progressives. And, mind, don't forget my warning."

And then the Fairy disappeared. A few moments later, and poor JOHN SMITH found himself sprawling upon the floor.

"Why, I do believe I have been asleep!" he exclaimed.

And then he woke up in good earnest, and hurried off to the polling stations, and voted for the Moderate candidates.

At least it is to be hoped he will!

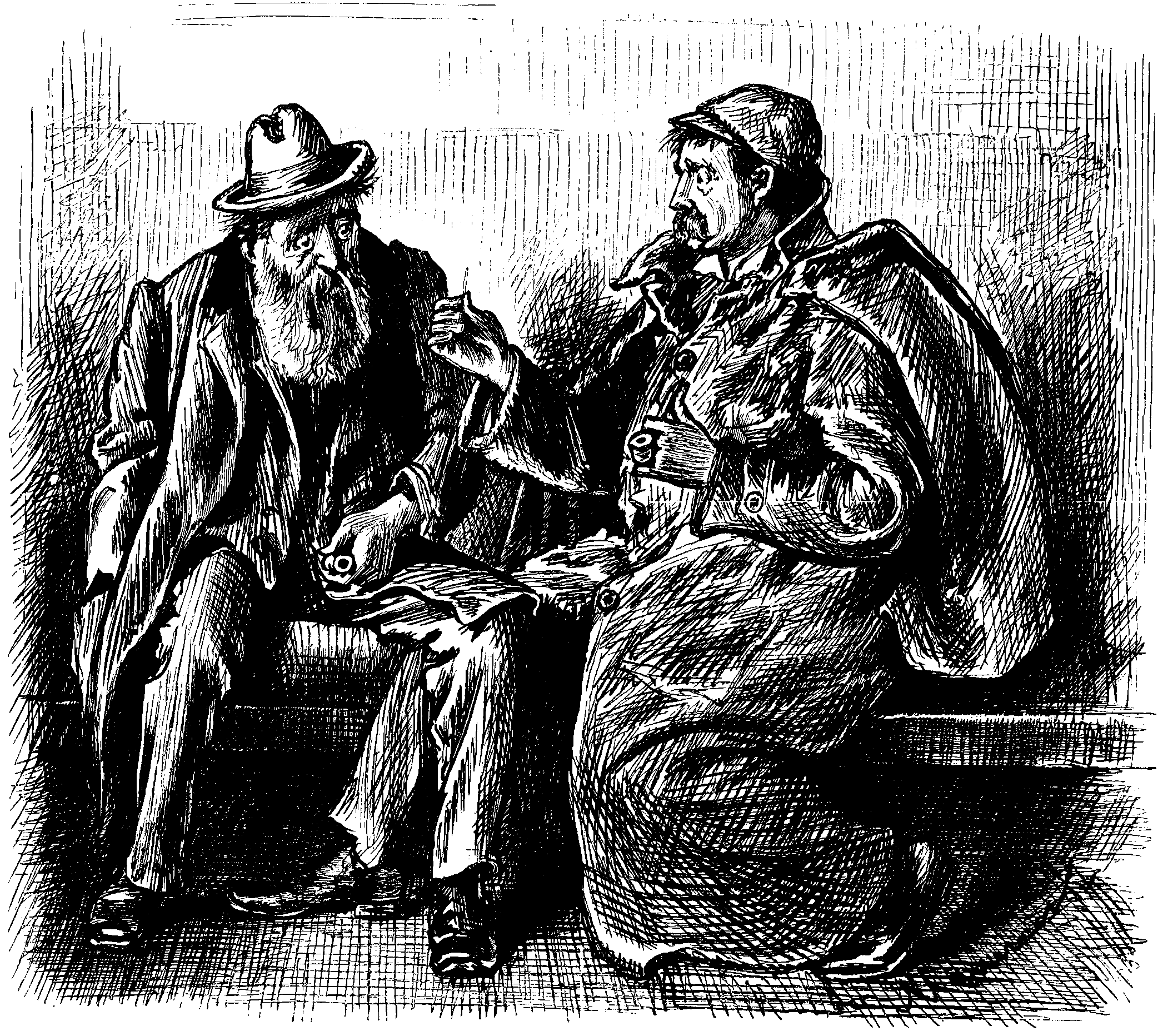

SCENE—A Third-Class Carriage. TIME—Three Hours before the next Station. DRAMATIS PERSONÆ— Jones and Robinson.

"IT'S THE LAST!—AND IT'S A TÄNDSTICKOR. IT'LL ONLY STRIKE ON THE BOX!"

"STRIKE IT ON THE BOX, THEN;—BUT FOR HEAVEN'S SAKE, BE CAREFUL!"

"YES; BUT, LIKE A FOOL, I'VE JUST PITCHED THE BOX OUT OF WINDOW!"

EXTRACTED FROM THE DIARY OF TOBY, M.P.

House of Commons, Monday, February 21.—"What a day he is having to be sure!" murmured the SQUIRE OF MALWOOD, looking across the table at the other eminent country gentleman who is our First Minister of Agriculture.

Truly a great occasion for CHAPLIN, and he rose to its full height. Just the same man he was six years ago when he from same place, drew lurid picture of the Empire staggering to its doom overweighted with Small Holdings. Now he is bringing in a Bill to establish Small Holdings, and recommends the expedient to House as crowning edifice of Empire's prosperity. At such a crisis some men would have blushed, however entirely foreign to their habit the pretty weakness might be. CHAPLIN, on contrary, made out in vague, but luminous, manner that he had been right in both instances. Indeed, the anxious listener had conveyed to him the conviction, still vague but not less irresistible, that this direct contradiction was peculiarly creditable to the Right Hon. Gentleman addressing the House, displaying a flexibility of genius not common to mankind.

CHAPLIN always looms large on whatever horizon he may appear. To-night, standing at Table introducing Small Holdings Bill, he seemed to swell wisibly before our eyes. Prince ARTHUR early in progress of the speech observed precaution of moving lower down Bench. By similar strategic movement, HENRY MATTHEWS drew nearer to Gangway. Thus CHAPLIN was, so to speak, planted out in Small Holding exclusively his own.

House anxious to hear particulars of Government measure, CHAPLIN, remembering old times when they used to jeer at his sonorous commonplaces uttered below Gangway, took a pretty revenge. Out of oration of fifty-five minutes duration, he appropriated twenty-five to general observations prefacing exposition of clauses of Bill. Just the same kind of pompous platitude conveyed in turgid phraseology, at which, in old times, Members used to laugh and run away. But CHAPLIN had them now. Like the wedding guest whom the Ancient Mariner button-holed—though as PLUNKET reminds me, the A.M. was meagre in frame, and CHAPLIN is not—the House could not help but hear. Once, when the orator dropped easily into autobiographical episode, described himself strolling about the fields of Lincolnshire, turning up a turnip here, drawing forth a casual carrot there, meditating on the days when

(Continued page 117)

every English yeoman went to morning service with a stout yew bow on his back, his quiver full of arrows; shot a buck on his way back (by permission of the landlord), and sat down to his midday meal flanked by a tankard of chill October—at this stage, it is true, there were signs of impatience amongst town-bred Radicals, who wanted to know about the Bill.

But it was very beautiful, and those who, from natural taste, inborn prejudice, or lamentable ignorance, did not care for it themselves, could not fail to enjoy the supreme delight the occasion brought to the Minister of Agriculture.

Business done.—Small Holdings Bill introduced.

Tuesday.—Two Right Rev. Bishops, Lord Bishop of ST. ASAPH and he of SALISBURY, in Peers' Gallery for two or three hours tonight; attracted by debate on Welsh Disestablishment. Bishop of SALISBURY couldn't restrain his astonishment at scene.

"One of the profoundest and most important questions of the day," he whispered in his right reverend brother's ear. "It is the attack upon the outworks. Wales carried by the Liberation Society, we shall have them leaping over the palings into our preserves. Should have thought, now, the House of Commons would have been seething with excitement; benches crowded; all the Princes of Debate to the fore; cheers and counter-cheers filling the place. Whereas there are not, I should say, more than eighteen Members present whilst the stout Gentleman down there is demonstrating how much happier Wales is under the benediction of the Church than she would be without. The whole thing reminds me, dear ST. ASAPH, of—er—well, of an eight o'clock morning service in inclement weather."

"You're young, brother SARUM," said ST. ASAPH, "young, of course I mean, in contradistinction to Old Sarum. When you've been a little longer in Parliamentary life, you'll understand things better. These empty benches, and the general appearance of being horribly bored presented by the small congregation—which I may say finds eloquent expression on the face of our friend JOHN G. TALBOT—simply mean that they have heard all these speeches before, and have made up their minds on the subject. They are ready to vote, but they will not remain to hear the speeches. As you say, in such circumstances it would appear more businesslike to take the vote at once, and get along with other work. But that is unparliamentary. This will be kept going till there is just time left before the adjournment to divide. Then you'll see how dear is this question to the hearts of our friends, and how virulent is the persistence of the adversary."

Turned out exactly as the Lord Bishop had said. After half-past ten, Members trooped down in scores. When Prince ARTHUR rose to continue the debate he was hailed with ringing cheer from embattled host. Pretty to see how gentlemen to right of SPEAKER, mustered for defence of the Church, were careful to contribute to fitness of things by wearing the clerical white tie.

"Very nice indeed of them," said Young SARUM, rarely out so late at night, but drawn back, after light repast, to watch the division taken. "I could wish that, instead of the superabundance of shirt-front displayed, our friends had selected more closely-buttoned vests, and that their coat-collar fitted a little higher. But we cannot have perfection, and the white tie at least indicates nice feeling."

Business done.—Proposal to disestablish Church in Wales negatived by 267 Votes against 220.

Wednesday.—PROVAND moved Second Reading Shop Hours' Bill, and, what's more, carried it against Ministers. CAMPBELL-BANNERMAN tells me that, though Scotch Members voted for Bill, result has cast a gloom over them. Expecting PROVAND would lose, they were all prepared to say, in casual way, "Ah, well, so the case is non-PROVAND." Some had, indeed, gone so far as commence to write letters home enshrining this joke. These are now, of course, waste-paper. Pity opportunity lost. Scotch language not rich in provision of similar openings for wit.

Business done.—Second Reading Shop Hours' Bill carried. Rare opportunity for Scotch joke hopelessly lost.

Thursday.—MIDLETON brought London Fog on again in Lords to-night. Asked the MARKISS if he would have any objection to appointment of Joint Committee to inquire into the matter? The MARKISS a great artist in words; suits his conversation to the topic. His reply decidedly misty; wouldn't say yes or no; talked about Joint Committees being a mysterious part of the Constitution; didn't know how they were to be appointed; hinted at rupture with Commons if proposal were made; wound up by saying that if Motion for Committee were submitted, he would do his best to induce their Lordships to adopt it.

Strangers in Gallery puzzled by this speech. But the Lords know all about it. STRATHEDEN winked at CAMPBELL, and both noble Lords wagged their head in admiration of MARKISS'S diplomacy; recognise deep design in involved speech and well affected hesitation.

MARKISS, I hear, vexed with me letting the cat—I mean the fog, out of the bag last week. But it's everybody's secret. The Government have made up their mind to go to the country on the London Fog. This Joint Committee will be appointed with least possible delay; a measure based on its Report will be carried through both Houses; everything will be ready for return of unsuspecting Fog Fiend next November.

"Sorry you mentioned it prematurely, TOBY," the MARKISS said, not unkindly. "But you only forestalled the announcement by a few days. It's been in my mind for months. The cry of Separation is growing a little shrill; Free Education hasn't done us any good; Small Holdings only so-so. The Fog's the thing! Grappling with that, all London rallies to our standard, and with London at our back we can face the country."

Curious instance of association of ideas and sympathy. So [pg 118] completely is mind of Her Majesty's Ministers occupied with this Fog problem, that to-night it got into House of Commons. LORD ADVOCATE brought in Bill allocating Scotch Local Taxation grant. Debate went on for six hours; at end of that time discovered that whole proceedings irregular. As involving money question, introduction of Bill should have been preceded by Resolution submitted to Committee of whole House. Debate abruptly adjourned; evening wasted; howls of derision from Radicals.

"Never mind," said Prince ARTHUR, cheerily. "Let those laugh who win. This is only another argument (perhaps not so accidental and undesigned as people think) in support of our new Fog policy."

Business done.—Night wasted in Commons. In Lords, light looms behind the Fog.

Friday.—News of Mr. G. speeding home over land and sea. All his friends on Front Bench been begging him to stay longer in the Sunny South. No need whatever for his return; things going on admirably; not missed in the least; shocking weather here; better stay where he is.

"Ho, indeed!" said Mr. G., pricking up his ears and a dangerous light flashing under his eyebrows. "I'm not wanted, ain't I? SQUIRE OF MALWOOD getting along admirably in my shoes; doing well without me; not missed in the slightest. Very well, then; I'll go home."

MACLURE, who has been in the confidence of great statesmen from DIZZY downward, tells me Mr. G.'s homeward flight was hastened by curious dream. Dreamt all his sheep were straying from fold; some going one way, others another; each bent on his own particular business. In vain Mr. G. leaping up and taking crook in hand, put hand to mouth and halloed them back to Home-Rule fold. They went their way, some even making for Unionist encampment, where Mr. G., moving heavily in his slumber, distinctly saw one sheep regarding scene through an eyeglass.

"Only a dream of course," Mr. G. said, when he set off in the morning for a twenty-mile walk. "But I think I may as well be getting back. Made up for the Session; fit for anything. Nothing could have been kinder or more watchful than Nurse RENDEL'S care of me; if I had been his son (which I admit is chronologically difficult), couldn't have been better done to. Only concerned just now for ARMITSTEAD. That young fellow, proud of his chickenhood of sixty-seven years, brought me out to take care of me, and freshen me up. Fancy I've worn him out; instead of his taking care of me, have to look after him! Shall be glad to get again within sound of Big Ben. Spoiling for a fight. HARCOURT done very well; but he'll have to tuck in his tuppenny and let me over into the Leader's place."

Business done.—Miscellaneous.

Rupert (just back from School, where he has been tremendously fagged). "LOOK HERE, ANGY, IF YOU BEHAVE DECENTLY, AND DON'T SMASH ANYTHING, YOU SHALL FINISH THE JAM—WHEN I'VE QUITE DONE!"

["It is better to do a stupid thing that has been done before, than to do a wise thing that has never been tried."—Mr. Balfour in the House of Commons.]

HEAR the great pundit; deem him not absurd,

He utters wisdom's latest, greatest word.

All coats, we know, are best when frayed with wear;

Trousers we love when most they need repair,

Boots without heels, completely lacking soles,

And hats all crushed and battered into holes.

Nay, we'll go farther, and, to prove him true,

Do all the vanished ages used to do.

We'll crop the ears of those who preach dissent,

And at the stake teach wretches to repent.

Clad cap-à-pie in mail we'll face our foes,

And arm our British soldiery with bows.

Dirt and disease shall rule us as of yore,

The Plague's grim spectre stalk from shore to shore.

Proceed, brave BALFOUR, whom no flouts appal,

Collect stupidities and do them all.

Uneducate our men, unplough our land,

Bid heathen temples rise on every hand;

Unmake our progress and revoke our laws,

Or stuff them full of all their banished flaws.

Let light die out and brooding darkness reign,

And in a word call Chaos back again.

Then, as we perish, we can shout with glee,

"Hail, hail to BALFOUR and Stupidity!"

SCREWED UP AT MAGDALEN.—Mr. G.B. SHAW had a lively time of it at Oxford. Fancy a whole bevy of Socialists all cooped up together under lock and screw. What a fancy-picture of beautiful harmony the mere thought conjures up. Burning cayenne pepper on one side, dirty water on the other, and loyal Undergraduates, screwed and screwing, all round them. Never mind, BERNARD. It was a capital puff for the Socialistic wind-bag, and one G.B.S. took care it should not be wasted.

"To set class against class is the crime of all crimes."

That's the dictum of FUSBOS, a type of our times;

Yet FUSBOS himself all his co-scribes surpasses

In rancorous railings concerning "the masses."

He thinks that all efforts injustice to right

Are inspired by mere malice and fondness for fight.

He might just as well urge that morality's rules

Set slaves against tyrants, or rogues against fools;

Or mourn that each new righteous law that man passes

Must set honest folk 'gainst the criminal classes!

"THE MEETING OF THE WATERS."—The Engineers of London and Birmingham have been requested, says the Daily Telegraph, to "lay their heads together," so as to see if an amicable arrangement cannot be effected. This is an instance where to have "water on the brain" is absolutely necessary. Odd to think that in this "water difficulty" are contained all the elements of a burning question; so much so indeed, that the Engineers who may be clever enough to solve the problem without getting themselves into hot water, may confidently be expected to follow up their achievement by proceeding to "set the Thames on fire."

QUEER QUERIES.—CURRENCY REFORM.—I see that the CHANCELLOR OF THE EXCHEQUER intends to "call in" light sovereigns. The sovereigns I have all seem to be tolerably heavy, so would there be any objection to my lightening them by taking some of the gold off, and keeping it? This would form a nice little "metallic reserve" for me, a thing which Mr. GOSCHEN seems to approve of. Would not an appropriate motto, to be inscribed on the new One Pound Notes, be—"Quid, pro quo?"—SLY-METALLIST.

TO A SKITTISH GRANDMOTHER. (AD CHLORIN.)

FORBEAR this painted show to strut

Of girlish toilet, manner skittish:

It may be Fin-de-Siècle, but

It isn't British.

To dance, to swell the betting rank,

To rival 'ARRIET at Marlow;

To try to break your husband's bank

At Monte Carlo,

Would ill beseem your daughter "smart;"

The vulgar slang of bacchant mummers,

If act you must is scarce the part

For sixty summers.

Let Age be decent: keep your hair

Confined, if nothing else, to one dye:

I'd rather see you, I declare,

Like Mrs. GRUNDY!

(What it may come to.)

["If we are obliged to go into the open market for our soldiers, and compete with other employers of labour, we must bid as highly as they do, in pay, hours of work, and general conditions and comfort."—Daily Paper on the Report of Lord Wantage's Committee.]

SCENE—A Public Place.

Sergeant KITE and a Possible Recruit in conversation.

Sergeant Kite (continuing). Then you must remember that we are exceedingly generous in the matter of rations.

Possible Recruit (pained). Rations! I suppose you mean courses! I find that in all the large firms in London the assistants have a dinner of six courses served, with cigars and coffee to follow. I couldn't think of joining the Army unless I had the same.

Sergeant K. (with suppressed emotion). If it must be so, then it must. Who's to pay the piper, I don't know! The Public, I suppose.

P. R. I should think so! Then as to drills. Really the number of these useless formalities should be largely decreased, and the hours at which they are held should be fixed with greater regard to the convenience of private soldiers. By the bye, of course I need hardly mention that I should not dream of enlisting unless it was agreed that I should never be called before 9.30 A.M. My early cup of tea and shaving-water might be brought to me at nine.

Sergeant K. (after an interval). Called! Early cup of tea! Shaving-water! Oh, this is too much!

P.R. (coolly). Not at all, my dear Sir, not half enough. There are other points I wish to mention. For example, do you allow feather-beds?

Sergeant K. Feather-beds!

P.R. Yes. A sine quâ non, I assure you. Then as to pay and pensions, and length of service. I would only accept an engagement by the month, with liberty to terminate it at any time with a week's notice.

Sergeant K. (with sarcasm). And you would wish to retire at a week's notice if war were declared?

P.R. (surprised). Certainly! Why not? "Peace with Honour" would be my motto. As to pay, of course you know what I could get if I went in for civil employment?

Sergeant K. No, I don't, and I don't see what that has to do with it. You surely would not compare the QUEEN'S service with the work of a beggarly counter-jumper?

P.R. Yes, I would. And as I could earn five shillings a-day easily in a shop, why, you will have to give me that, with a pension (as I might do better) of ten shillings a-day after six years' service.

Sergeant K. Any other point you would like to mention?

P.R. Yes, there is one other. Why should a labourer be able to get damages from his employer when injured, and a soldier be unable? The principle of the Employers' Liability Act must be extended to the Army, so that if any Commanding Officer made some stupid blunder in battle, as he probably would do, and I were to be hurt in consequence, I might sue him when we got back to England. You understand my point?

Sergeant K. Oh, quite! But what would there be to prevent every soldier present at the battle from suing also?

P.R. Nothing at all. Of course they would all sue. So no General must be permitted to go into action without first of all depositing in the High Court at home security for costs if defeated,—say half a million or so.

Sergeant K. (with forced politeness). Well, I'm glad to have heard your views. I'll mention them to my Colonel. They are sure to please him.

P.R. Yes, but don't keep me waiting long for his reply. My offer only remains open till to-morrow morning.

Sergeant K. Oh—!

[The remainder of the gallant Sergeant's observations are not necessary for publication, neither would they be accepted as a guarantee of his good faith. Exit to recruit.

FROM very early days, the days, or nights, of The Battle of Waterloo and Scenes in the Circle, with the once-renowned WIDDICOMB as Master of the Ring, Mr. Punch has ever been particularly fond of the old-fashioned equestrian entertainment. The Ring to which he has just made allusion is, it need hardly be added, The Circus, and The Book is a novel by Miss AMYE READE. Mr. P. is not sweet upon any gymnastic and acrobatic shows in which the chances of danger appear, and probably are, as ten to one against the performer; and especially does he object to children of very tender years being utilised in order to earn money for their parents or guardians by exhibiting their precocious agility. Mr. P. approves of the ancient use of the birch as practised at Eton a quarter of a century ago, and he is quite of the Wise Man's opinion as to the evil consequences of sparing the rod; which proverbial teaching, had it been practically and judiciously applied to Master SOLOMON himself (the ancient King, not the modern Composer) in his earliest years, would probably have prevented his going so utterly to the bad in the latter part of his life. So much, as far as corporal punishment is concerned, for the education of youth, whether in or out of the circus school. But girls, as well as boys, are trained for this circus business, gaining their livelihood by acrobatic performances. Does Mr. Punch, representing the public generally, quite approve of this portion of circus and acrobatic training? To this he can return only a qualified answer. His approval would depend, first, on the natural but extraordinary capability of the female pupil, and, secondly, the method of training her. As a rule, he would prefer to keep her out of it altogether: and, as to the boys, he certainly would defer their public appearance until they were at least sixteen; their previous training having been under the supervision of a responsible inspector. Then as to the training of animals for the circus business. If the training system means "all done by kindness," that is, by unflinching firmness and a just application of a considerately devised system of equally balanced rewards and punishments, then Mr. P. approves; but where cruelty comes in, whether in the training of child or beast, Mr. Punch would have such trainer of youth punished as Nicholas Nickleby punished Squeers, in addition to imprisonment and fine; and for cruelty to dumb animals Mr. P. would order the garotter's punishment and plenty of it. Having professed this faith, Mr. Punch, after thus "arguing in a Circle," returns to his starting-point, and would like to know how much of truth there is in Miss AYME READE'S story entitled, Slaves of the Sawdust? As literature it is poor stuff, but as written with a purpose, and that purpose the exposing of alleged systematic cruelty in training children and dumb animals for the circus-equestrian acrobatic life, the book should not only attract general notice, but should also lead to a Commission of inquiry, or to some united action of all responsible circus-managers against the author of this work, which would result in either the said managers or the authoress being "brought to book." Mr. Punch hath spoken. Verb. sap.

NOTICE.—Rejected Communications or Contributions, whether MS., Printed Matter, Drawings, or Pictures of any description, will in no case be returned, not even when accompanied by a Stamped and Addressed Envelope, Cover, or Wrapper. To this rule there will be no exception.